For two decades, the coffee industry seemed on an unstoppable march towards a globalised future dominated by US and European brands exporting coffee and café culture to new audiences around the world. But today, many of these successful businesses are under severe pressure as high costs erode profitability and long-held business models are undermined by soaring coffee prices. Tobias Pearce explores how coffee businesses in consumer markets are adapting to new economic realities – and whether the global coffee industry as we know it will ever be the same again

The 2010s were a golden era for the business of coffee and hospitality. Large coffee chains, roasters and independents alike were riding high on coffee’s booming cultural capital. Investors were hungry to buy into an industry that had demonstrated over 20 years of growth and showed no signs of slowing. With quality on the rise, developing markets in Asia and the Middle East presented lucrative new frontiers for international growth.

Missed Coffee’s New World Order: Part One?

Catch up here.

Times have changed. In 2020, the global pandemic marked the beginning of a new phase of profound disruption and cost pressures that have become the new norm for the coffee industry. High inflation is another hangover from an overstimulated global economy during the pandemic.

“We’ve seen an uneven recovery from inflation and countries have stabilised their economies to different levels,” says Dr Vesselina Ratcheva, a social scientist specialising in cultural insights and social trends.

Coffee demand may be stronger than ever, but many businesses are under sustained pressure from record-high commodity prices and operational costs.

Meanwhile, consumers in developing coffee markets, such as China and India, long coveted as growth markets by Western coffee businesses, are gravitating towards affordable home-grown competitors. Fast-growing coffee chains, such as China’s Luckin Coffee and Cotti Coffee, Thailand’s Café Amazon and Malaysia’s ZUS Coffee, are outmanoeuvring many international competitors at home.

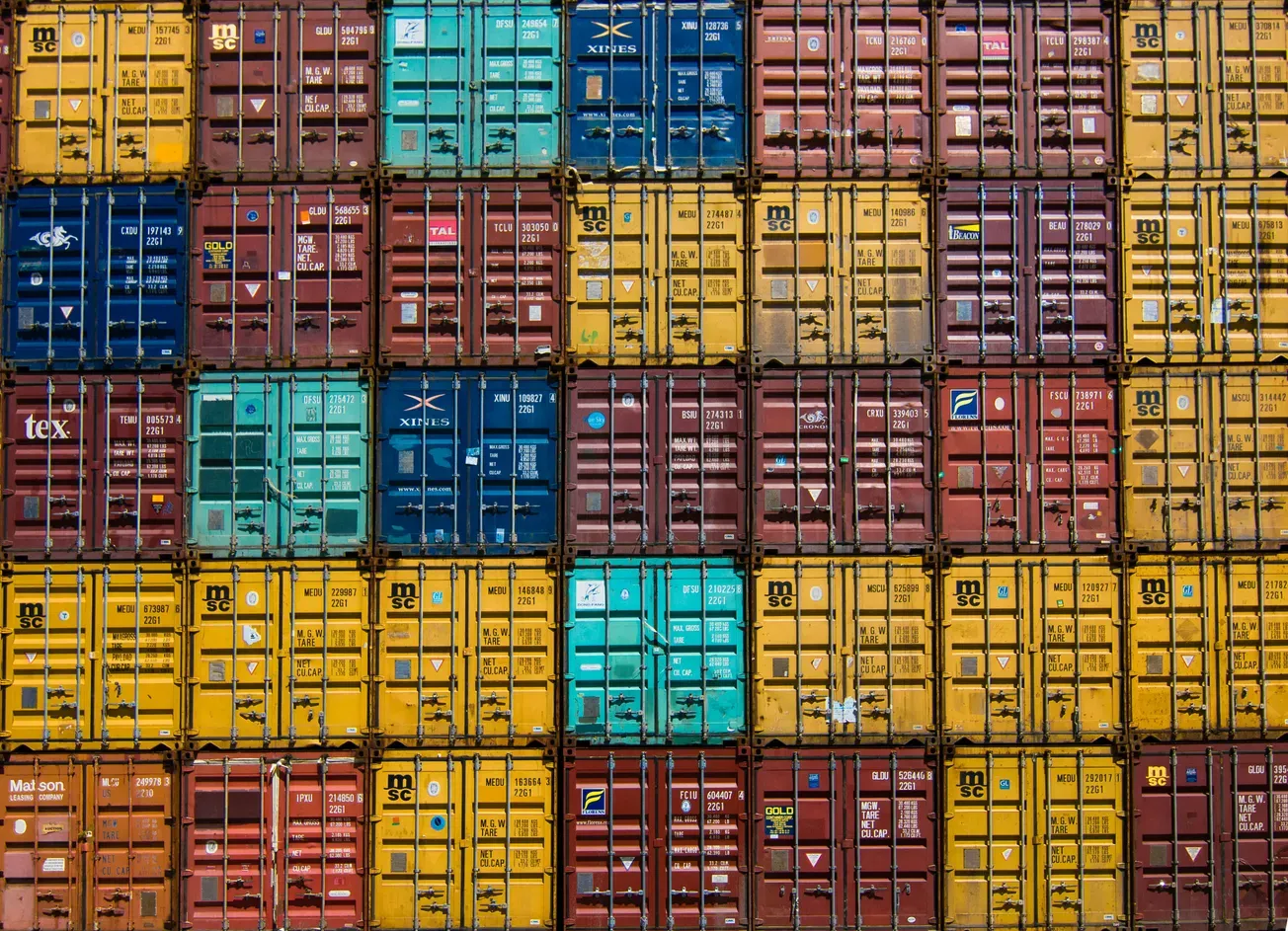

The coffee industry may be larger than ever – but it is becoming increasingly atomised amid rising national sentiment and retreating globalisation.

“There’s a greater preference for prioritising regional or national diversity, and that comes from a very specific place – which is the sense that some elements of globalisation didn’t work out for all economies equally, or sufficiently equally, and for all populations,” observes Ratcheva.

In this rewiring of the global economy, many are asking if big coffee as we know it has gone off the boil. At one point, coffee made up 70% of JAB Holding Company’s $34bn investment portfolio. However, JAB has since pivoted away from coffee, including the sale of its controlling stake in JDE Peet’s, with insurance businesses now making up nearly 50% of its portfolio.

Facing soaring coffee and cocoa prices, Nestlé has announced a $3.7bn efficiency drive, including 16,000 job cuts – 6% of its global workforce. Coca-Cola, too, is reevaluating its coffee strategy, and Starbucks is struggling with flat sales in the US and China, its two largest markets.

“This is definitely not the time to compromise quality”

– James Hoffmann, co-founder, Square Mile Coffee Roasters, author and content creator

The softening appeal of these mid-market coffee brands stems from the rising cost of a daily coffee purchase, driven by inflation, greater competition and market saturation. It also mirrors shrinking middle-class wealth in the US and Europe, where the notion of coffee as an affordable luxury is being challenged like never before amid stagnant wage growth.